Last week, we talked about the need for salespeople to build and expand their selling skills in order to adapt to, and compete with, artificial intelligence. This week, let’s talk about exactly HOW to develop your selling skills. “But, Troy, I work on my selling skills all the time!” No, you probably don’t, if you’re like most salespeople.

I ran a poll on the biggest LinkedIn sales group. I asked, “On the average, how much time per week do you spend improving and practicing your sales skills, not counting time you spend selling?” The results were about as I expected: “Less than one hour” – 48%; “1-2 hours” – 32%; “2-5 hours” – 13%; “more than 5 hours” – 7%. That old 80/20 rule really is looking valid on this one. So, how should you be practicing?

My recommendation is this: Pick one critical skill of selling, and work on it each week. Next week, pick a different one, and so on. That will keep you from getting bored and falling into a rut. The critical skills are:

Prospecting: Work on your approach. There’s no prospecting approach that can’t be made better; in many cases, making it shorter makes it better. Your initial approach statement should be 10-15 seconds – no more. That goes for telephone prospecting (you do that, right?) or live, face to face prospecting. Refine it, hone it, improve it, and test it.

Questioning: The most important skill set in questioning. Develop two new, great questions to ask a prospect. Practice them, and more importantly, practice LISTENING ACTIVELY to the answers. Repeat and refine.

Presenting: You already know that I don’t like one size fits all presentations. However, I do like a “modular presentation,” where you are prepared at a moment’s notice to present on different benefit/feature combinations, or aspects of your service. Think of it as a mental “slide deck” where the slides can be rearranged, inserted, and deleted on the spot. Practice one “slide” per week.

Proposing: Present price and terms confidently and in a way that doesn’t invite distrust or uncertainty.

Closing: Practice getting comfortable with asking simple, to the point, closing questions – and then shutting up.

Handling objections: Make a list of common objections, and then come up with your first, best response to each one. Practice clarifying, isolating, and resolving objections.

As I said, rotate these around to stay fresh and incrementally build your skills over the long haul. And practice. Most salespeople don’t practice skills except in front of the customer. That’s dumb. In front of the customer, mistakes cost you money. In your office, it costs you nothing except a little time and a little pride (if anyone else sees).

And here’s the mentality you should use in your practice. Some of you know that I am a former and reformed wrestling fan (today’s product is just insulting to the intelligence, in my opinion). Still, I like listening to podcast interviews of past wrestling personalities. It’s mind candy for when I drive, and I drive a lot – but occasionally, something really profound emerges.

One such profundity came from a wrestler and wrestling trainer named Dr. Tom Prichard. The host and Prichard were discussing a particular dangerous wrestling move that had been botched on a recent show, and could have caused paralysis or even death. Prichard said, “People shouldn’t do moves that they don’t know how to do.”

The host agreed and said, “Practice till you get it right, right?”

Prichard said, “Nope. Practice until you can’t get it WRONG.”

Wow. That’s pretty profound, isn’t it? There’s a big difference, as I thought about it, between “until you get it right” and “until you can’t get it wrong,” and it’s the difference between conscious thought and habit. I encourage you to follow Dr. Tom’s advice. Whatever technique you are working on, practice it to the point that you can’t get it wrong, and you won’t. How much does that take?

It depends on you and your mental makeup. Studies show that habits form at 21 repetitions. Maybe it takes that much for some techniques; maybe it takes less than others. I’d suggest that when you realize that you aren’t having to invest the same level of conscious thought to get through a particular technique, you’ve got it. Then, when you’re in front of the customer, that conscious thought can be invested in paying attention to the customer, their reactions, and their words.

Because – even though they aren’t practicing the way you are – the customer is always the star of this particular show. Don’t forget it, and keep working to develop your selling skills.

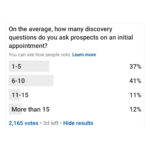

Are you asking enough questions? A couple of weeks ago, I ran a poll on a very popular LinkedIn group. The poll question was simple: “On the average, how many discovery questions do you ask a new customer on an initial appointment?” If you’ve read any of my work at all, you know that I believe that the root of good things in selling is asking a lot of good questions; in fact, questioning is the longest unit in

Are you asking enough questions? A couple of weeks ago, I ran a poll on a very popular LinkedIn group. The poll question was simple: “On the average, how many discovery questions do you ask a new customer on an initial appointment?” If you’ve read any of my work at all, you know that I believe that the root of good things in selling is asking a lot of good questions; in fact, questioning is the longest unit in